A Subversion of the Exorcism Genre: Michael Peterson on SHADOW OF GOD

Ahead of the 2025 Calgary Underground Film Festival, I connected over Zoom with Michael Peterson, the Calgary-based director behind Shadow of God, a new exorcism film making its Canadian premiere at CUFF before arriving on Shudder this April as part of the Halfway to Halloween lineup. While this was our first formal interview, Peterson’s work has been familiar to me for some time now – especially his producing role on “Ming’s Dynasty”, the CSA-nominated CBC Gem series co-created by my longtime friend Antony Hall.

We actually ended the interview by falling into a long tangent about that show – how good it was, how frustrating it is that it didn’t get a proper second life. And, without making this entire piece about a cancelled series, I’ll just say this: my father, who was in his mid-60s at the time, binged the entire thing in two days. That kind of cross-generational appeal isn’t easy to fake.

Peterson has also remained a fixture in Calgary’s indie film scene, recently leading a “So You Want to Be a Producer” workshop with the Calgary Society for Independent Filmmakers. Our conversation ranged across a lot of ground – from casting and visual design to the strange realities of making a film that tests what people are willing to believe.

Check out 10 Must-Watch Films at CUFF 2025

Tickets for Shadow of God at CUFF 2025 Here

What is Shadow of God About?

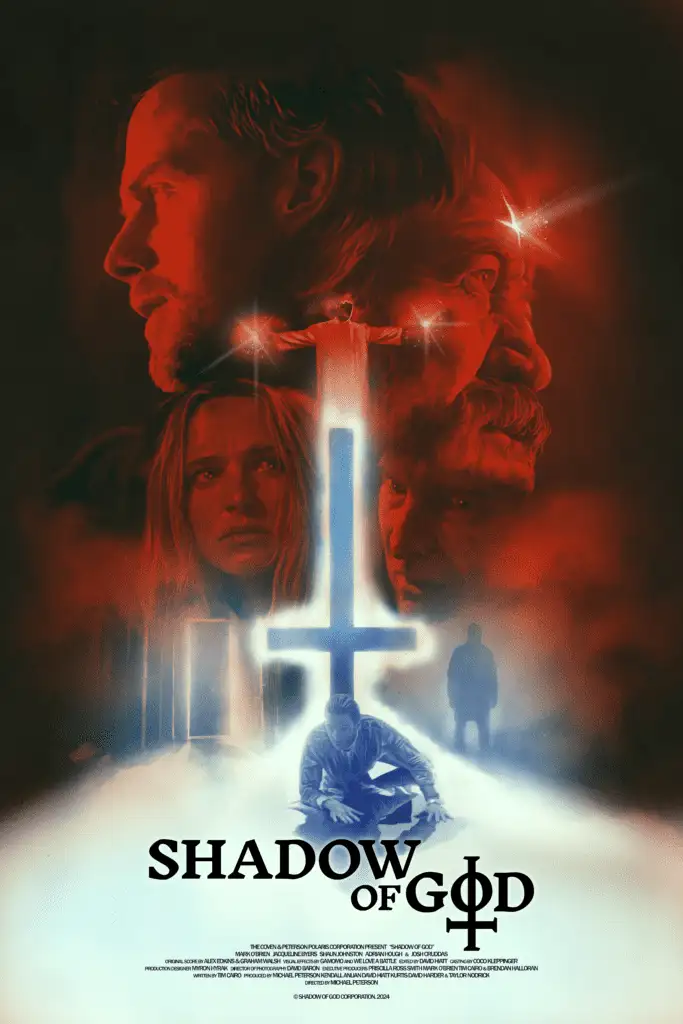

The film opens on familiar ground: a priest mid-exorcism. But Shadow of God quickly sidesteps expectation. It follows Father Mason Harper (Mark O’Brien), a Vatican exorcist who returns home after several of his colleagues are killed under mysterious circumstances. There, he reconnects with an old friend and is stunned to find his father, Angus – long presumed dead – has reappeared. Stranger still, Mason comes to believe Angus isn’t possessed by a demon, but by something holy.

Rather than dismissing genre convention, the film builds within it. “Exorcist movies have been done so many times,” Peterson told me. “It’s a very predictable subgenre. But this was dealing with what I thought were provocative ideas.” Shadow of God honours the visual and thematic language of exorcism films – ritual, religious dread, the burden of faith – but repurposes those tools to question the binaries they usually reinforce.

That questioning wasn’t abstract. Some crew members left the project after reading the script. “There were a handful of crew that were like, ‘Oh, I can’t work on this,’” Peterson said. “I don’t think it supports my belief system. I don’t like what it’s saying.” Rather than seeing that as a setback, Peterson took it as a sign they were onto something. “To me, that was amazing – and a thumbs up that we were probably on the right path.”

As someone who didn’t grow up in a deeply religious context, I found this surprising. You forget how destabilizing it can be – for some people – to suggest that a divine presence might act violently, or that holiness might not be inherently good.

The Development of Shadow of God

Peterson first received the script in 2018 from Tim Cairo, whose film Off Ramp screened at CUFF in 2024. “It was one of those projects where I thought, ‘This is cool – I want to figure out how to do this,’” he told me. “But I didn’t think I’d direct it.”

That initial hesitation wasn’t surprising. Peterson has worked more often as a producer over the past few years, though he’s been moving back toward directing – something we circled back to later in the conversation. The script went through several rewrites, shifting between financing partners along the way. At one point, it looked like they had secured funding through a South African financier. Then, while Peterson was mid-flight, the deal collapsed. “When I left, everything was fine,” he said. “By the time I landed 20 hours later, it was off the table.”

Eventually, The Coven stepped in. Known primarily as a distributor – Terrifier 2 and 3 being recent examples – this was their first time producing a feature outright. Their stipulation was clear: it had to shoot that year. “We were supposed to be starting prep in two or three weeks,” Peterson said. “So we just jumped in.”

It wasn’t ideal timing. But the project had stuck around for a reason.

The Coven and Shooting in Calgary

When The Coven came on as producers and locked in the production timeline, the choice of location had to be pragmatic. Prince Edward Island and Colombia were both considered, but as the schedule closed in, they became less feasible. “Eventually it did come down to speed and predictability,” Peterson said. “Those weren’t worth taking those risks on with the timeline we had.”

Calgary was already part of the plan. Post-production would be there, and several of the crew were local. “It was never not connected to here,” he told me. “This is where I make stuff most often. This is where I live.”

Still, that familiarity doesn’t flatten the film into something regionally generic. Shadow of God doesn’t scream Alberta, but it doesn’t hide it either. The landscapes, the sense of distance, the tone – all of it carries a specific kind of weight that feels rooted without feeling provincial. Just like it holds to the structure of an exorcism film while pushing against its limitations, the project reflects where it was made without needing to explain it.

Casting Choices in Shadow of God

Peterson first met Mark O’Brien back in 2019, during a CUFF script reading organized by filmmaker Rob Grant. They hadn’t worked together, but when O’Brien’s name came up during casting, Peterson didn’t hesitate. “His name was on a list and I was like – he’d be my top choice,” he said.

Still, there was a moment of doubt. O’Brien had just directed a religious drama of his own and had appeared in another exorcism film not long before. “I wondered if this would feel too familiar,” Peterson admitted. Instead, O’Brien jumped at the script. “These are themes he’s clearly drawn to,” Peterson said.

The more unexpected casting came with Shaun Johnston as Mason’s father. Best known as Grandpa Jack on Heartland, Johnston isn’t the first name that comes to mind when you picture a spiritually tormented patriarch. But Peterson dug a little deeper. “He’s got this theatre background – he started a company in Edmonton and did plays like Love and Human Remains,” he said. “He’s done edgy stuff.”

That tension between what audiences expect from Johnston and what he delivers onscreen became part of the appeal. “He’s still hungry,” Peterson said. “Really playful, but intense in the right way.” At one point, he joked about doing a Heartland fan event, with a Grandpa Jack signing followed by a screening of Shadow of God. Which – now that I think about it – feels like a personal mission I should take on. If even a handful of Heartland fans stumble into this film unprepared, it’ll be worth it.

Ghostkeeper, Metz, Holy Fuck, and the Score

The score in Shadow of God isn’t just background – it drives nearly every moment of tension in the film. Peterson had hoped early on to bring in Shane Ghostkeeper, whose sound he’d loved while producing another feature. “That score was my favourite thing about that movie,” he told me. “They weren’t coming from horror. So they brought this outsider sensibility that just hit differently.”

But by the time Peterson reached out to confirm, Ghostkeeper was heading out on tour, and the timing didn’t line up. Shane still ended up in the film, though, playing a supporting character named Randall. In one sequence, his character fiddles with the truck radio and lands on a track from Ghostkeeper’s own new album – a twangy, country-leaning release that subverted expectations in the same way Shadow of God tries to upend its genre. “It’s an Easter egg,” Peterson said. “No one else will know, but I thought it was funny.” It’s also a Calgary-specific nod for anyone paying attention – both to the music scene and to how subversion often starts close to home.

Peterson also mentioned that he might’ve played a small role in nudging Shane toward acting. “I think I told him to come out for an audition years ago,” he said. “But I don’t want to take credit – he’s just always had presence.”

After our conversation, I revisited a 2023 red carpet interview I did with Ghostkeeper at the Calgary International Film Festival. When I asked how he got started in film, he did, in fact, point to Michael Peterson (and Julian Black Antelope) as the two who encouraged him to audition for “The Agreement” – his first role.

The score ultimately came from Alex Edkins and Graham Walsh, best known for their work with Metz and Holy Fuck. While the music still fits within the horror space, Peterson liked that they weren’t coming in from a strictly genre-trained place. “Sometimes horror scores start to echo each other – same soundscape, same instrumentation,” he said. This one still has the atmosphere, but it carries a different pulse: hints of punk, electronic edges, and moments that feel slightly off-centre – enough to keep you unsettled without pulling focus.

Behind the Scenes of Shadow of God

Two scenes in Shadow of God stood out – for both me and Peterson. The first is a tense conversation with Lucifer, filmed in a way that’s intentionally disorienting. “The camera is probably one inch from their face,” Peterson said. “And every time they move a quarter of an inch, they’re out of focus.” It was shot with a long lens that flattens space, forcing the eyelines to hover – close to the audience, but never quite at each other.

“I wanted to have eyelines that are almost looking at the audience,” he said. “Using lenses the opposite of how you often use lenses and how they’re used in the rest of the movie… so it feels different without feeling totally out of the norm, just off a bit.”

The other standout sequence is what he called the Satan birthing scene. In the original script, it leaned heavily on dream logic and surreal visual flourishes – “kind of weird images behind,” he said – but Peterson found that approach too on-the-nose. “To me, fixing it with certain things felt like it would take away some of the magic and the mystery.”

He worked with his effects team to build something more tactile: a practical black membrane, calf birthing gel, and a shot setup he diagrammed himself. “It’s a very simple shooting setup,” he explained. “But also extremely effective.” For Peterson, these were the scenes that mattered most. “Almost always,” he added, “the simple shit is the best shit.”

What’s Next for Director Michael Peterson and CUFF 2025

Peterson has no shortage of projects in the pipeline. He’s directing a tropical-set crime thriller next winter and developing a true crime docuseries about a South African doctor whose path leads to Calgary. He’s also produced a number of other features – including This Too Shall Pass, the new film from Rob Grant, which is also screening at CUFF this year.

As for the festival itself, Peterson’s approach is loose. “There isn’t a movie I don’t want to see,” he told me. “I’ll just pop into whatever I can.” What he’s most looking forward to, though, is the part you can’t schedule: “Seeing friends visiting with their films, meeting the ones I don’t know yet – that’s my favourite part.”

Shadow of God Trailer

Read More: