EBONY AND IVORY Intentionally Disrupts the “Biopic” Formula | Interview with Jim Hosking

Ahead of the Canadian premiere of Ebony and Ivory at Calgary Underground Film Festival (April 19), I spoke with director Jim Hosking over Zoom. This marks his return to CUFF after opening the 2018 festival with An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn, and this time, he’ll be attending alongside actors Sky Elobar and Gil Gex.

Ebony and Ivory is a surreal, entirely fictional imagining of the first meeting between Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder, whose 1982 duet “Ebony and Ivory” became both a commercial success and a cultural curiosity. While the song climbed charts with its message of racial harmony, it was also roundly mocked for its saccharine lyrics and simplistic symbolism.

Hosking’s film avoids all of that.

Check out 10 Must-Watch Films at CUFF 2025

Tickets for Ebony and Ivory at CUFF 2025 Here

What is Ebony and Ivory About?

Ebony and Ivory is not a biopic. It’s not even about the song. What it is, however, is an off-the-wall, slow-burn character piece that invites discomfort, absurdity, and unexpected moments of surrealism.

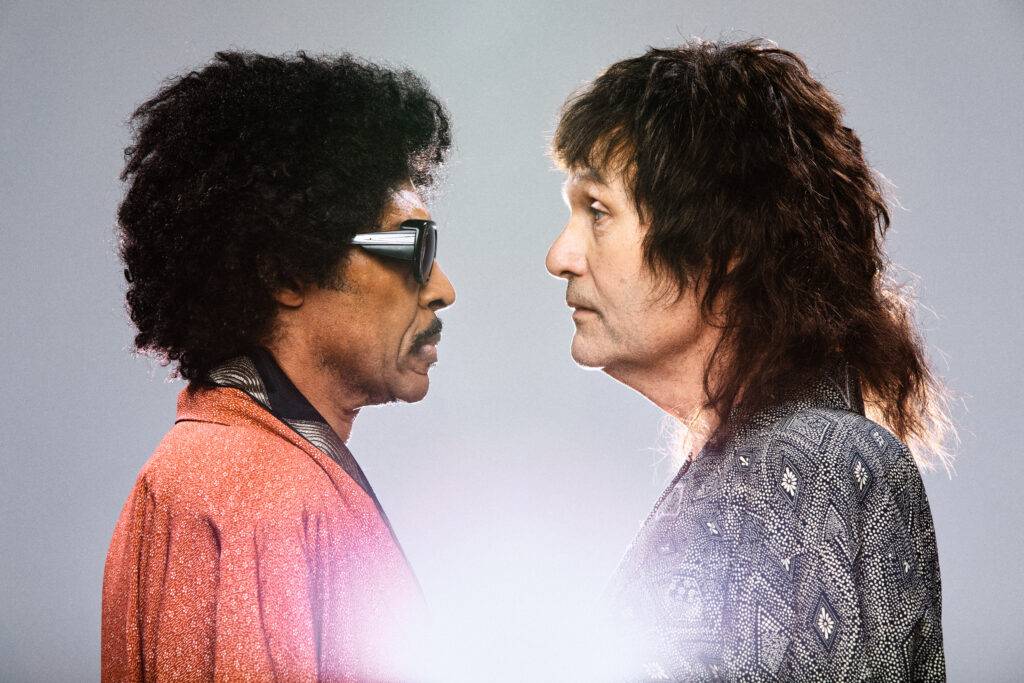

“They don’t really look anything like them, they don’t sound anything like them, there’s nothing true in the film. The music has no bearing on the sound of the song Ebony and Ivory,” Hosking tells me, half laughing. The casting itself seems to signal this early. Gil Gex and Sky Elobar – longtime Hosking collaborators – are significantly older than the real-life McCartney and Wonder would have been in 1982. Their delivery is exaggerated, almost cartoonishly theatrical at times. It’s immediately clear: this is not a tribute.

Set in a remote cottage near the Mull of Kintyre—a nod to McCartney’s real-life ties to the region, and his 1978 song with the band “Wings”—the film follows Stevie (Gex) as he arrives by boat to visit Paul (Elobar). What unfolds is not plot, exactly, but atmosphere. Repetitive, stilted conversations drift in and out of meaning. Scenes loop back on themselves. The rhythm of the film resists momentum on purpose.

“I think I just wanted to make something small and strange,” Hosking says. “It was during COVID, and I had this idea stuck in my head—the genesis of a song I’m not particularly attached to. That made me laugh.”

Sky Elobar and Gil Gex as Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder

The script, which Hosking wrote himself, was treated less as gospel and more as scaffolding. “Even there were parts of the script that I’d completely forgotten that I’d written,” he says. “I’d get the pages for each day and think, ‘God, I don’t remember.’” “Or I’d think we’d already filmed something, but it was just a different version of the same rhythm.” While there wasn’t much improvisation from the actors themselves, Hosking would regularly feed them alternative lines mid-scene or pull them off-script to intentionally disorient them.

That disorientation wasn’t a bug – it was a feature. Hosking says he often tries to unmoor his performers, subtly nudging them out of their comfort zones. Sky Elobar arrived on set meticulously prepared, having studied McCartney interviews and mastered every line. So naturally, on his first take, Hosking told him, “Now could you do it as if you’re from Liverpool?”

Gil Gex, meanwhile, approached the shoot with nervous energy and little sleep. “Every morning at the hotel, he’d come up to me with the script and ask to talk through the same bit,” Hosking recalls. “He always wanted to break the dialogue into smaller chunks. I’d tease him – ‘You need to know it or you’re wasting everyone’s time.’”

The Comedy of Ebony and Ivory

The balance between discomfort and discovery fuels the film’s tone. At one point, Gex began repeating the phrase “shit and fuck” as if it were one word. “I found it so funny,” Hosking says. “Then I couldn’t stop saying it either. I just locked in.” That compulsive repetition – something that shouldn’t be funny, but becomes funny through insistence – is part of what gives Hosking’s work its energy.

“When something feels like the wrong strategy, then I’m drawn to doing it” – Jim Hosking

“I don’t think of myself as a comedy director,” he says. “I don’t really watch comedy. I think I find things funny because they’re not funny – or because they’re trying not to be.”

Which is to say: Ebony and Ivory will not be for everyone. It doesn’t offer punchlines or resolutions. There’s no ironic winking to reassure you. What there is, however, is a distinct tone, born from tension and creative autonomy. Hosking isn’t trying to anticipate what audiences want – he’s actively resisting it.

Directing Jim Hosking on “Making Films for Himself”

“When I finished editing this, I realized I never once thought about how anyone else would receive it,” he says. “That probably hasn’t always been the case. But this one just felt singular.”

In today’s climate – where filmmakers are often urged to shape their projects around audience expectations or funding requirements – that’s a rare admission. Hosking’s refusal to play that game might explain why his films remain so distinct. It also explains why he doesn’t often read reviews. But he did once.

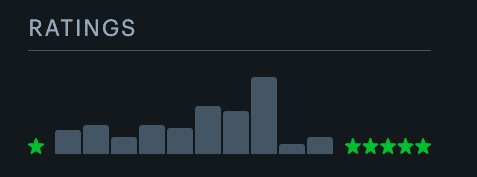

“I looked at Letterboxd recently,” he admits. “I was surprised how divisive this was. Some people loved it. Some people really didn’t. I thought everyone would get it.”

Still, the surprise doesn’t change his strategy. “It’s more fun to ambush people,” he says. “Not just show the film to those who already know what to expect.”

And ambush, Ebony and Ivory does. The pair may or may not transform into goats. There is product placement so aggressively absurd it becomes its own character – like “Wee Billy’s Big Wee Fizzy Beer.” And, in true Hosking fashion, prosthetic penises make an appearance.

“I can see that it could look like I’m absolutely obsessed with them,” he says, laughing. “But I swear I’m not. There were seven years between [Ebony and Ivory and The Greasy Strangler]. But this time, I messaged Sean Baker and asked where he got the one for Red Rocket. He connected me with this guy who makes the best in the business. I picked two. I thought they were average (they were 7 inches). He said, ‘If you want average, go smaller.’ But I didn’t want it to be a joke about small penises.”

Ebony and Ivory as a Contradictory Manifestation of Anxiety and Freedom

Even with some large prosthetics swinging around, there’s a sincerity beneath the absurdity. Hosking isn’t just being provocative – he’s expressing something instinctive. And once that instinct is fulfilled, he’s done.

“Some filmmakers love going to festivals and watching their film four times,” he says. “For me, it’s hell.”

That’s the contradiction of Jim Hosking. In daily life, he describes himself as anxious, easily overwhelmed by traffic noise or small disruptions. Yet, when he’s making a film, the noise disappears. “I get very OCD about the edit, the soundtrack – everything becomes hyper-specific,” he says. “But the process itself? That’s when I feel free.”

It’s a paradox reflected in the film itself: controlled chaos. Deep anxiety wrapped in comedic looseness. A constant shifting between intentional discomfort and surprising intimacy.

What is Next for Jim Hosking?

Hosking currently has four projects in development. One, he says, is “not a comedy at all.”

“To call it horror would be too narrow,” he says. “It’s more of a nightmare. Quite erotic. Very different.”

Still, he resists clean definitions. “I try to make choices that echo the original impulse,” he says. “And if that impulse leads somewhere strange, I’m okay with that.”

Strange, after all, is Hosking’s default setting. Whatever genre his next project takes on, one thing’s certain: it will not follow the formula.

For fans of his work, that’s part of the draw. For newcomers, a word of advice – don’t go into Ebony and Ivory expecting a music biopic.

Unless you want your reality gently, hilariously shattered.

Read More: