After Yang is Kogonada’s masterful follow-up to his 2017 directorial debut in Columbus. Adapted from the short story “Saying Goodbye to Yang” by Alexander Weinstein, Kogonada has expanded upon the original and brought his own insight to the source material. While this film was first shown at the Cannes festival in July of 2021, Kogonada went back to the editing room to make some improvements before releasing it again in March of 2022. This release was extremely limited, with only 24 theatres in North America taking on the film for its opening weekend. Fortunately, After Yang is now available for rent on several platforms, so it is finally accessible to the masses.

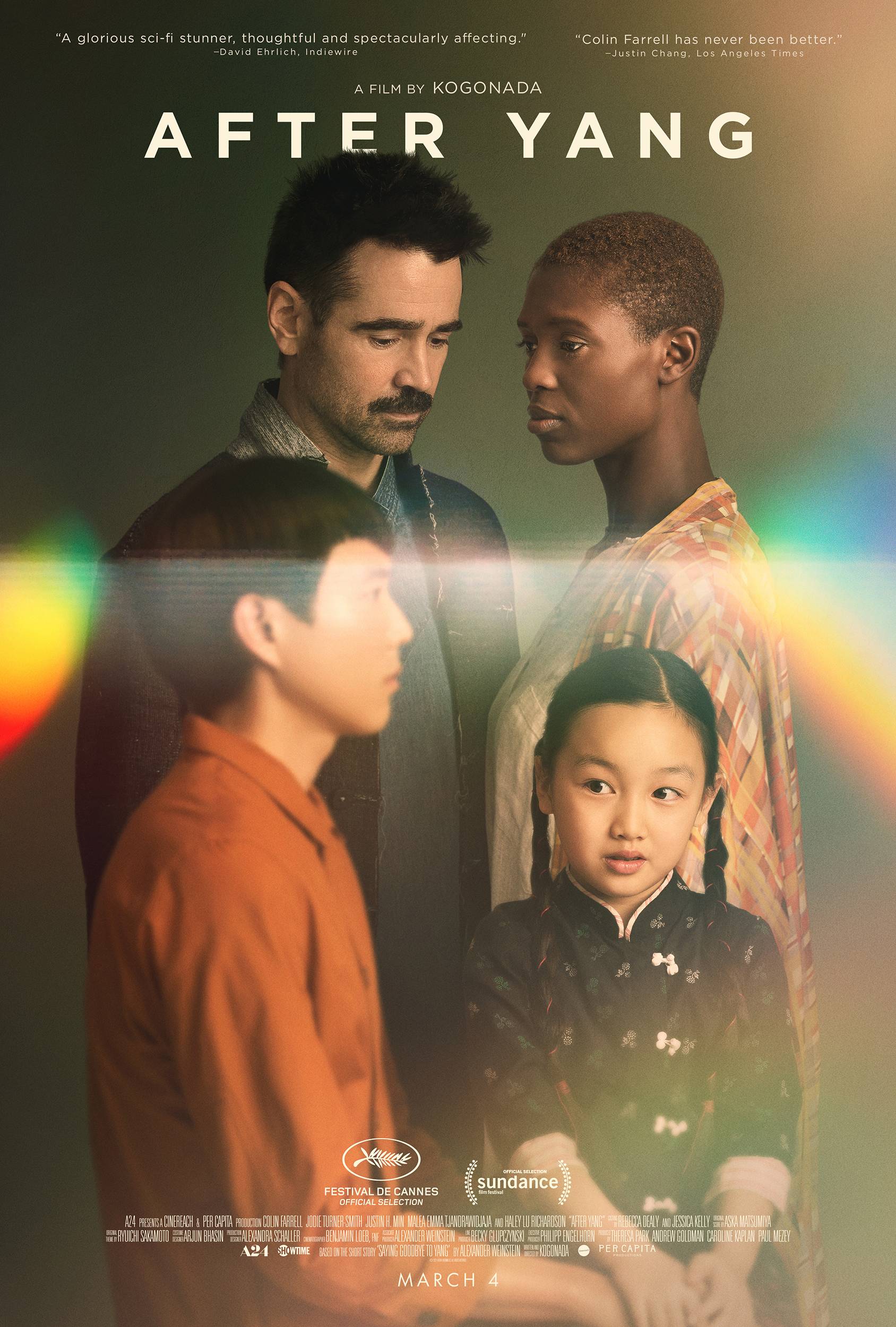

In After Yang, we join two parents and a daughter at some indeterminate time in the future as they struggle to come to terms with the loss of their A.I “technosapian” who, by all intents and purposes, was part of the family. While on the surface this concept does not appear to be particularly novel, Kogonada’s direction swiftly and certainly sets this film apart from its A.I-focused counterparts.

Kogonada himself is a bit of an enigma in the world of cinema. The name Kogonada is a pseudonym adapted from the mid-20th century Japanese screenwriter Kogo Noda, and his legal birth name is not widely known. In fact, Kogonada has spent most of his career working behind the scenes, creating video essays for outlets like the Criterion Collection and Sight & Sound. As a result, his art stands solely as the art itself, rather than being shrouded by some grandiose filmmaking persona.

In any event, after watching After Yang, audiences will surely be wanting to learn more about this mysterious filmmaker. At the risk of sounding hyperbolic, this film is one of the most magical meditations on humanity and the beauty of the world that I have seen in years. As a lover of Kogonada’s previous work, Columbus, I should not have been surprised by this, yet I still found myself in almost perpetual awe as each shot unfolded.

It should be noted that Kogonada has not only directed his two feature films, but has also been responsible for the writing, and most importantly, the editing of these films. In this way, he has been able to enact his vision from beginning to end. Specifically, some of his editing techniques are used not simply to create coherence in the narrative structure but actually serve as narrative devices in themselves. For example, Kogonada’s use of colour gives the viewer a deeper thematic insight into the film than most other filmmakers can provide with explicit dialogue. At times, he leans into the greens of nature, and at other times, he incorporates an otherworldly hue that highlights the magic in each beat. That being said, his editing is not so heavy-handed that it forces the audience to feel a specific way, but instead provides space for each individual to attach their own emotional connection to every frame.

Beyond the fairly obvious use of colour, Kogonada also demonstrated his mastery of film in more subtle ways. He has an innate sense of timing, with each shot being held for the perfect duration – not a second too long or too short. He also incorporates some unique visual effects, most notably during futuristic “face time-esque” calls between Jake (Collin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith). These calls are shown in a way that does not focus on the technology being used, but rather reiterates the disconnectedness that the characters are experiencing in these moments.

Kogonada’s direction certainly stands out, but the performances from the cast are also worth acknowledging. Collin Farrell has moved on past his “bad boy of Hollywood” persona in recent years, working with directors such as Yorgos Lanthimos in some slower, more nuanced roles, and his work here with Kogonada continues that trend. In some ways, this is Farrell’s film, as his journey ultimately leads to a sense of self-discovery that in turn is shared with the audience. Understated, this role illustrates Farrell’s ability to take a seemingly simple script and create something meaningful for the audience.

Jodie Turner-Smith, Justin H. Min (Yang), and Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja (Mika) also provide strong supporting performances, with Tjandrawidjaja stealing the show on several occasions, mostly in the soft and tender moments when she shares a song or speaks to the void in Mandarin as she grieves the loss of Yang. This is most aptly captured when she expresses that Yang can “hear [her] even when [she] whispers”. While, in a literal sense, this shows the technological ability of technosapians, more importantly, it reinforces the idea that not all things of merit need to be shouted, and her performance is evidence of this.

I would be remiss if I did not mention Aska Matsumiya’s haunting score here as well. She has done a brilliant job at creating a soft, fluid, and at times ethereal space for the characters to encompass. This is perfectly aligned with Kogonada’s editing to create a dreamlike space while remaining grounded.

This film held me in an enraptured state from the opening shot to the final credits. In fact, the opening credit sequence is one of the most fun and engaging openings to a film in recent memory. This is juxtaposed by the final shot of the film, leading into the end credits, which packs a tremendously emotional punch. While I already envision some complaining about the “pacing” of the film being a tad on the slow side, I think that those who launch that complaint may be missing the essence of After Yang.

At its core, this film serves as a reflection on life and encourages the viewer to examine the moments from their own lives that bring them meaning. Not every meaningful moment comes from thrills and excitement. Sometimes the moment is a simple appreciation of the beauty around us. Sometimes it is driving alone with our thoughts. Sometimes it is a broken reflection from a window. Sometimes it is nothing more than stillness. Ultimately, Kogonada’s intent here is not to create some artificial sense of action, but rather to offer an opportunity for us to stop and breathe as the world continues to move around us.

After Yang could have very easily turned into a thriller exploring the rise of big tech, corporate greed, and the lack of privacy for consumers, but instead, it remains rooted in humanity. It may not be the type of film that comes to mind when most think about a science fiction world full of A.I and clones, but it is exactly the film that it needs to be. Floating effortlessly between the real and the imagined, Kogonada asks questions about what it means to be human but also takes his own experiences as an Asian-American to ask questions about more specific cultural identities as well. Ultimately, his messaging compels us to find beauty in the every day.

By the end of the film, we may still not have a clear answer to what it means to be human but at the very least, After Yang reinvigorates the human desire to search for that meaning. Without entering deep into spoiler territory, this is perhaps best encompassed when Yang asks Jake what he likes most about tea. Jake makes a connection to a documentary that he had watched (which is an actual documentary that can be seen here) and explains that it was the “searching that compelled [him]”. While he enjoys the taste of the tea, it is the journey to get the tea that brings the most value. While the meaning here is obviously metaphorical, it did also leave me with a real hankering for some loose-leaf tea.

After Yang is currently available to rent on various platforms, including Google Play, Amazon, Cineplex, and YouTube. If you are looking for a meditation on humanity, or simply wish to slow down and appreciate the beauty of the world around you, this is worth adding to your list. Take a breath, close your eyes, and enjoy.

Trailer:

Link to my Letterboxd:

Very excited to watch this one!

It’s worth it!

I am intrigued and would.like to watch! Great review.

I hope that you enjoy it!

Pingback: Top 22 Films of 2022 - Points of Reviews