Cinematographer Martim Vian on LOVE, BROOKLYN and How Director Rachael Abigail Holder Evolved His Work

Love, Brooklyn is the debut feature film from Rachael Abigail Holder and tells the intertwined stories of three Brooklyn residents navigating careers, love, loss, and friendship. Bringing Holder’s vision to life required cinematographer Martim Vian to push beyond his usual approach and embrace new perspectives. From frequent static shots and unconventional lighting to capturing the authentic Brooklyn backdrop (complete with garbage cans and graffiti), Vian stepped out of his comfort zone to align with Holder’s bold ideas.

I had the chance to speak with him about his experience working on Love, Brooklyn. He opened up about stepping away from his “bag of tricks,” the delicate process of visually integrating Brooklyn into the story, and the technical decisions that helped shape the film’s unique aesthetic.

Love, Brooklyn is Premiering at Sundance 2025 on January 27th, 2025

Cinematographer Martim Vian on His Journey and Working with Rachael Abigail Holder

ADAM MANERY:

You’re well-studied across the globe at some prestigious institutions. Was cinematography always the plan?

MARTIM VIAN:

Film was always the plan as a kid. I wanted to be an animator, and my dream was to work for Walt Disney. As I grew up, the movies I watched evolved into live-action. I went to the National Film School in Portugal out of high school, but I didn’t know cinematography existed. That’s where I discovered the role.

The camera always attracted me to filmmaking. There are so many pictures of directors behind the camera that I thought directors were the people behind the camera. I wanted to be a director, but when I realized they were not the ones working the camera, I shifted to cinematography.

What was it like working with Rachael Abigail Holder on Love, Brooklyn?

It was great. Rachael is an artist—a true artist. She had a vision for the movie, in all departments, and the things she wanted to do weren’t always the most common. For me, there was a road of discovery. We’re on a tight schedule and tight budget, so you come up with tricks as a cinematographer to get things done with whatever constraints you’re in. Those become a safe place. When a director asks you to do things differently in a way you haven’t done before, you’re suddenly in uncharted territory.

Initially, that was scary for me. But the more I listened to her and the more I followed her lead, the more my work evolved and the better it got. It was good for me to get out of my bag of tricks.

How Rachael Abigail Holder Brought New Visual Ideas to Love, Brooklyn

What were some of the ideas Rachael had that pushed you out of your comfort zone?

Initially, she wanted to shoot the whole movie with one lens, which was scary but also exciting. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to do it. At the last minute, we were given the option to add a second camera. In general, there were a lot of very composed and static shots with one lens. She wanted a lot of front light and a lot of hard light, which are things that felt risky as a cinematographer.

We did some camera tests. We had an actress we took out to a park, and we shot the actress in backlight, frontlight, and sidelight. The goal of that test for me was to show Rachael how the backlight was so much better, but it turned out that the frontlight was great, and that’s what she wanted. She was right. We shot it at 4 p.m., so it was a low sun, coming in at the right angle, and the front sunlight was gorgeous.

There were two huge green dumpsters full of graffiti. The first thing I did was ask them to move the dumpsters, but Rachael loved the dumpsters: “They are Brooklyn.”

There were things I kept discovering through her that changed my perception of how I should be doing things. The reality of our film production ended up throwing some of our prep away, so we didn’t get to do all of those things. Still, I love how Rachael took me out of my comfort zone, and my work evolved because of it.

As cinematographers, our brains go to what they know and what’s safe, but discomfort can be a good thing, and it’s the role of the director to push you there.

There are three central characters in Love, Brooklyn. Did you adapt the visual language for each character or keep these visuals consistent throughout?

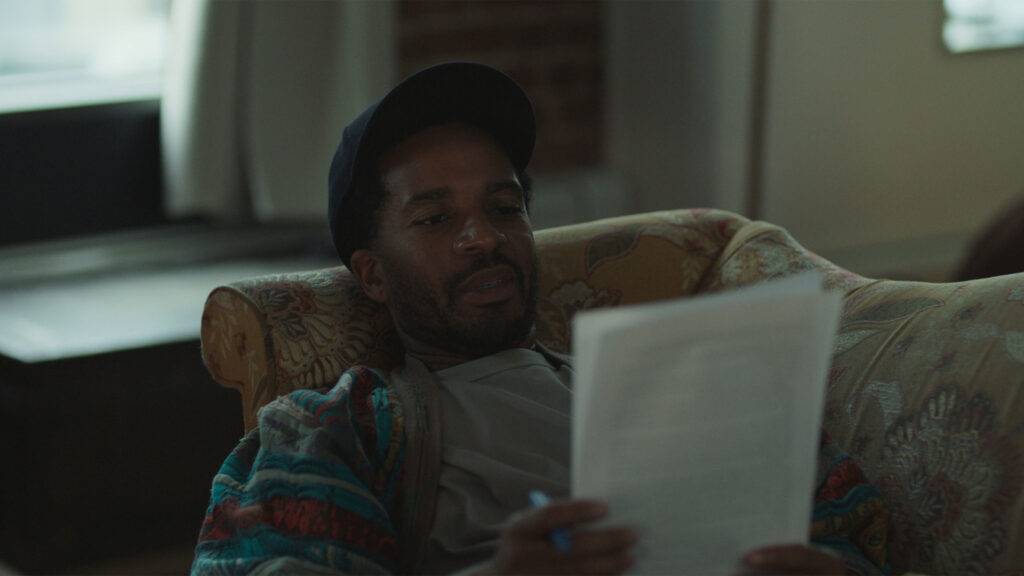

The movie is mostly written from the perspective of one character, Roger, played by André Holland. For Rachael, the important thing was to bring up the other two characters as much as Roger. Because of this, the approach was about trying to make this everyone’s story. There are a few pieces of coverage that weren’t in the script that allowed us to stay with Nicole Beharie‘s and DeWanda Wise‘s characters after Roger exited the scene. Those little things were important to Rachael to bring their stories to the screen and let us be in their point of view for a second. Visually, we weren’t trying to separate the stories. It’s a place and moment in time. It’s more about contextualizing everyone within their spaces and with each other.

As the title, Love, Brooklyn, suggests – much of this work is an ode to Brooklyn. How did you incorporate the city into the film?

The movie was pushed back several times, so we were on prep twice, and we had soft prep for almost two years. As a non-American and non-New Yorker, I was interested in discovering Brooklyn, especially through the eyes of Rachael. Rachael grew up in Brooklyn, so the question was, “How do we depict Rachael’s Brooklyn? What is Rachael’s Brooklyn?”

A lot of the trees in Brooklyn have wooden structures around them that feel like construction. My first instinct was, “We have to get rid of those. They don’t look good on screen.” Rachael overheard me saying that to our location person, and she said, “What are you talking about? This is Brooklyn. All the trees have that.” The same thing happened in a park. There were two huge green dumpsters full of graffiti. The first thing I did was ask them to move the dumpsters, but Rachael loved the dumpsters: “They are Brooklyn.” So, much of the process was discovering Brooklyn through Rachael’s eyes and experience, and staying true to that.

Call Me by Your Name as a Visual Inspiration in Love, Brooklyn

What references or visual inspirations did you and Rachael Abigail Holder have for Love, Brooklyn?

Visually, Rachael’s biggest reference was Call Me by Your Name, which didn’t have anything to do with Brooklyn. It had more to do with the immediacy of the camera and the lighting. There’s a lot of sunlight in Call Me by Your Name, and it’s a summer movie, so that was our strongest reference.

I like references that aren’t direct matches because they leave space for interpretation. The business is getting too self-referential now that it’s so easy to pick up frame grabs from websites and pause things. The decks that cinematographers used to make had paintings. I once met a cinematographer who was talking about a deck he made, and he had fabric in it. He was talking about how he brought pieces of fabric to talk about texture, and it was so interesting.

I like the references you have to put together to create something. Because then, even though you’re always copying, you don’t feel like you are. Rachael talked about how she wanted the movie to be “sharp.” That scared me. That’s not a quality I’m usually looking for. The more we talked about it, the more I realized she wanted things to feel “defined.” It wasn’t necessarily high resolution or micro detail. She wanted to see people’s features, to feel the texture of the trees. She didn’t want things to get fuzzy.

The Equipment Behind the Visuals of Love, Brooklyn

You shot Love, Brooklyn with two cameras — the ARRI Alexa Mini and the ARRI Amira, using the Master Primes with both. You also used some diffusion filters. How did you land on this specific equipment?

We decided that we wanted a lot of depth of field. This allowed us to bring Brooklyn into the movie without constantly cutting to Brooklyn. Instead, Brooklyn was the tapestry underneath everything. As much as possible, I was shooting the movie at an ƒ/8, ƒ/11, ƒ/16. Even in the night scenes, I rated the camera at 1600 ISO so I could be at a ƒ/4 – most of our night scenes were shot at a ƒ/4. I had to figure out how to bring that definition without bringing sharpness in.

There are so many choices now with cameras and lenses, so one of the things I like to do is limit my choices. You can do that through testing or your own experience. With lenses, I tend to not let myself get too excited by the offer. Master Primes are lenses I know very well. They have more personality than they get credit for, especially if you throw some direct light at them.

As a cinematographer, you’re trying to serve the movie, the story, the director’s vision, and you want to almost disappear.

I had never shot the Master Primes at an ƒ/11 or ƒ/16, and I knew they had been designed to perform better wide open. So during testing, I shot the Master Primes at these f-stops and they started breaking apart in subtle but interesting ways. In the park, the trees in the background were getting this fuzziness that was still sharp because we were at a ƒ/16 on a 25mm, but the slight blur of the lens gave them a quality that felt a little “70s” — like the lens was less optically perfect.

I also knew we had some night exteriors, where I couldn’t light them. So the scenes of Roger riding a bike through a park are shot at ƒ/1.3, but that’s the only time I used the lenses wide open. Still, knowing I had that option on a tight schedule and budget gave me comfort.

Regarding the Amira, it has the same sensor as the Mini. I love the Amira for how it’s built — it feels more like a “camera” to me. You can put it on your shoulder and operate it that way, so the Amira was a good complement to the Mini.

The diffusion allowed me to break apart the image a little more. I rarely use diffusion. I played with this specific diffusion on a previous project, and what I liked is that it helped with the perceived sharpness of a digital camera without blooming the highlights or adding fuzziness. I used very low-grade diffusion, so it was part of the recipe to create a “look.”

The diffusion in Love, Brooklyn is subtle, and I like it that way. But it does make a big difference if you see a “before” and “after.” This specific diffusion is fascinating because it doesn’t add much blooming and helps with faces. It’s a movie about people, and I thought a little diffusion would help blend everything.

I did a big test on a previous movie where I compared a lot of diffusions, and when you viewed it next to other diffusions, it seemed like it was doing very little. But when you compare it to the baseline, it was doing something special.

Quick Questions: Directors, Films, and What to Watch at Sundance 2025

If you could work with any director, who would it be?

Sam Mendes. I watched American Beauty the year before I went to film school, and it blew me away. Directors who come from stage work—people like Sam Mendes and Mike Leigh—are some of my favorites. The movies are very much about the characters, but they’re also visual in different ways. Sam Mendes went on to do a James Bond movie, which is the other side of the metal. If you ask me, “What’s your dream movie on either end?” It’s a James Bond movie to Revolutionary Road – something like that.

What is a film you are in awe of, from a cinematography perspective?

There are cinematographers whose work fascinates me, either because I think they’re working in a similar way as me or because they’re working in a completely different way. I watched Fanny and Alexander recently, and it’s a brand-new 4K scan, and that movie could have been shot today. To me, that’s incredible. Sven Nykvist shot it in the early 80s, but it could have been shot today. That says something about not going with the “hype” of the moment—making a movie in a way that’s truthful to the story and doesn’t feel dated.

As a cinematographer, you’re trying to serve the movie, the story, the director’s vision, and you want to almost disappear. You want your work to be the support for whatever is happening. That’s something I try to do—not be too flashy. But then you see Fanny and Alexander, and it’s a gorgeous movie, and the great masters do that. They create an image that is constantly stunning, but it’s also there to serve the story. They’re not saying, “Look at me, look at me.”

What films will you be checking out at Sundance 2025?

I was excited to see Kahlil Joseph‘s movie, Blknws: Terms & Conditions, but it sounds like it’s being pulled. I’m not sure what’s happening there, so I’m still holding on to the ticket just in case. (note: Blknws was temporarily pulled from Sundance 2025, but it was able to premiere after Rich Spirit and BN Media acquired the film). I’m going to try to see everything in competition, and some “Midnight” movies seem great—Opus looks incredible.

Discovering new movies and talent is what I love about these festivals. You come out excited about your job and inspired to keep doing it.

More About Martim Vian (from: www.martimvian.com)

Lisbon-born cinematographer Martim Vian’s passion for filmmaking ignited early in life. His diverse body of work spans major streaming platforms to independent cinema.

In 2025, Vian’s cinematography will be on display at the Sundance Film Festival in Love, Brooklyn, a U.S. Dramatic Competition official selection directed by Rachael Holder and produced by Steven Soderbergh.

Vian’s upcoming projects include the romantic comedy You’re Dating a Narcissist starring Marisa Tomei.

Prior to these projects, he contributed to the visually striking Netflix series VOIR (2021), produced by David Fincher. His credits also include the romantic comedy Alone, Together (2022) with Katie Holmes and the Hulu psychological thriller Clock (2023). In 2024, Vian shot the indie film Lazareth, marking Ashley Judd’s return to the screen.

Vian’s career extends to commercials, music videos, and feature films. He has collaborated with renowned brands like Levi’s, Axe and Gucci and worked on music videos for artists including Haim, Moses Sumney, Vince Staples and Bastille.

He studied Cinematography at the National Film School Conservatory and FAMU, the Czech National Film School. He graduated from American Film Institute (AFI) with a Master’s degree in Cinematography.

Fluent in Portuguese, English and French, Vian is a member of the Portuguese Society of Cinematography, AIP, since 2007.

Read More: